Computer Graphics

Bézier Curves I

Course Evaluation

- Feedback possible till December 15th, 18:00

- Please participate

- Add additional comments

- Link

Last Time: Procedural Modeling

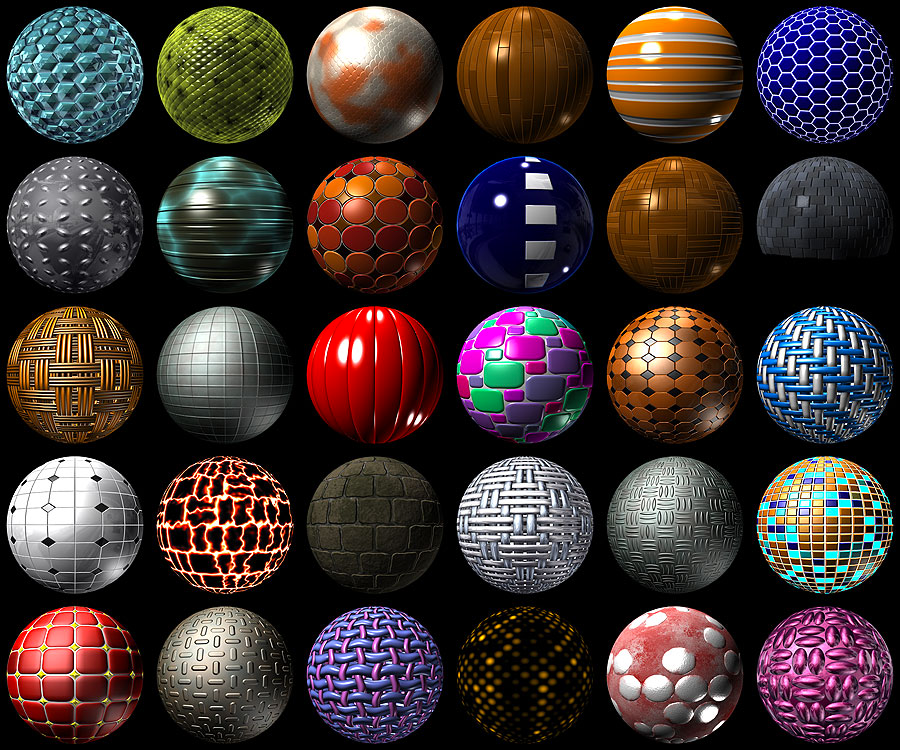

Procedural Techniques

- Ubiquitous in graphics

- texturing, modeling, animation, etc.

Procedural Approach

- Why?

- automatic generation on the fly

- compact representations

- infinite detail

- unlimited extent

- parametric control

- Particularly suitable for models resulting from processes that are repeating, self-similar, or random

- Challenges: artistic control, debugging, efficiency

Noise Functions

- Function \(\mathbb{R}^n \to [-1, 1]\), where \(n = 1,2,3...\)

- Desirable properties

- No obvious repetition

- Rotation invariance

- band-limited

- frequencies stay finite

- more structure than white noise

- efficient to compute

- reproducible

- Fundamental “primitive” or building block of most procedural synthesis approaches

Classic Perlin Noise (1980s)

- Interpolate random gradients with Hermite interpolation

Fractal Brownian Motion (fBm)

- Spectral synthesis of noise function

- Progressively smaller frequency

- Progressively smaller amplitude

- Typically Perlin noise is used

- Each term in the summation is called an octave

- Each octave typically doubles frequency and halves amplitude

Fractal Dimension Example: Koch Curve

\[ \begin{aligned} D &= \frac{\log(N)}{\log(r)} \\ \end{aligned} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} \\ N &= 4 \\ r &= 3 \\ D &= \log(4)/\log(3) \\ &= 1.26185951... \end{aligned} \]

Multifractals

- Fractal system which has a different fractal dimension in different regions

- Heterogeneous fBM

- Typical implementations don’t just spatially vary the \(H\) parameter

- One strategy: scale higher frequencies in the summation by the value of the previous frequency.

- Many possibilities: heterogenous terrain, hybrid multifractal, ridged multifractal

- See the Texturing & Modeling book [Ebert et al.] for details

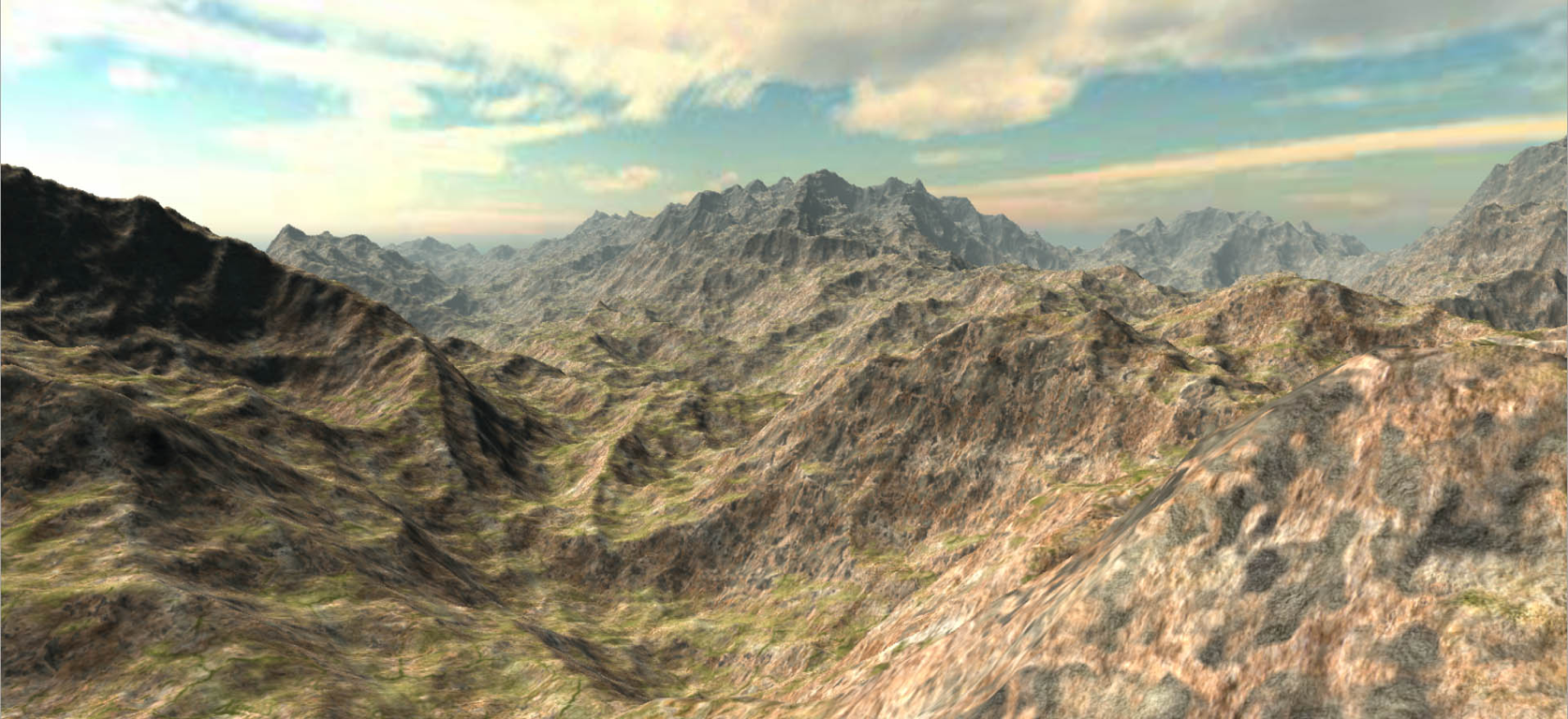

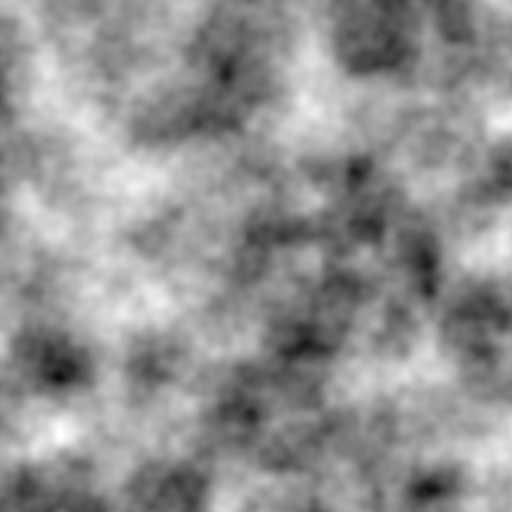

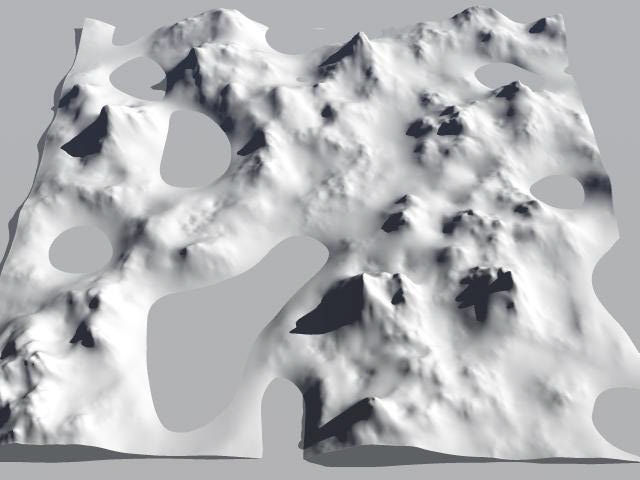

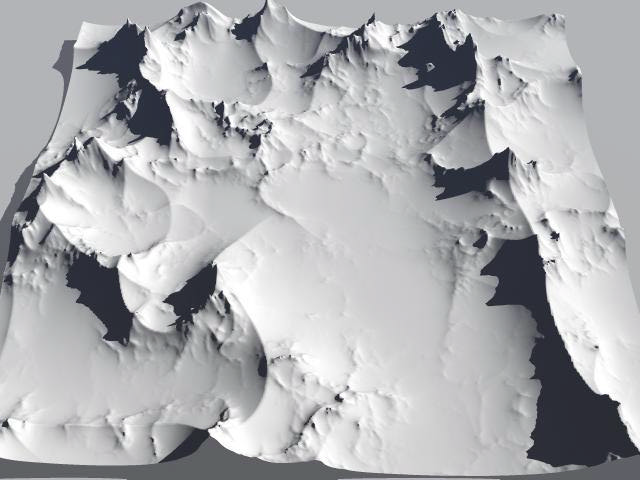

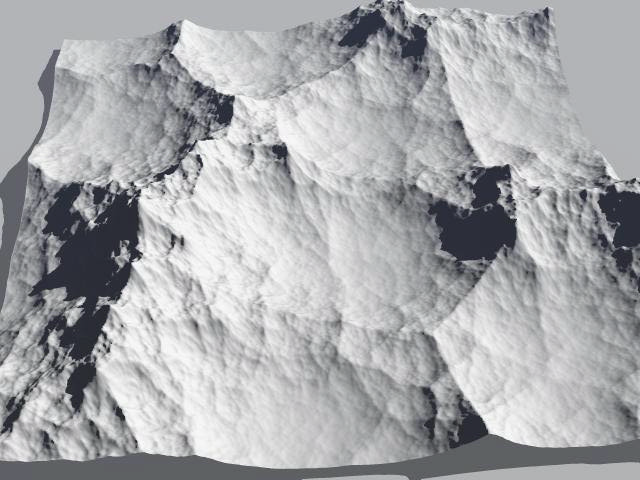

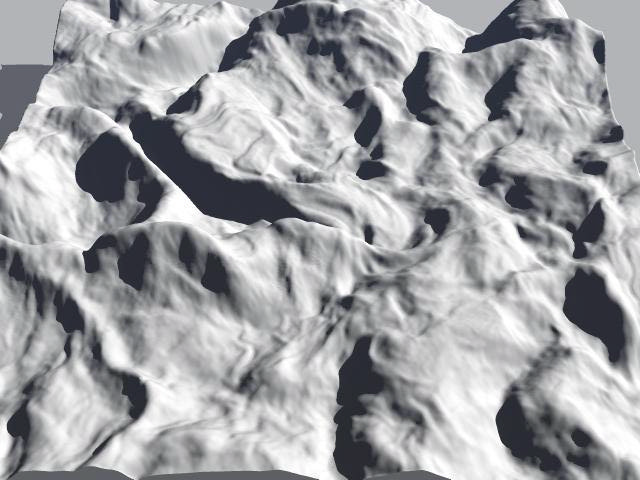

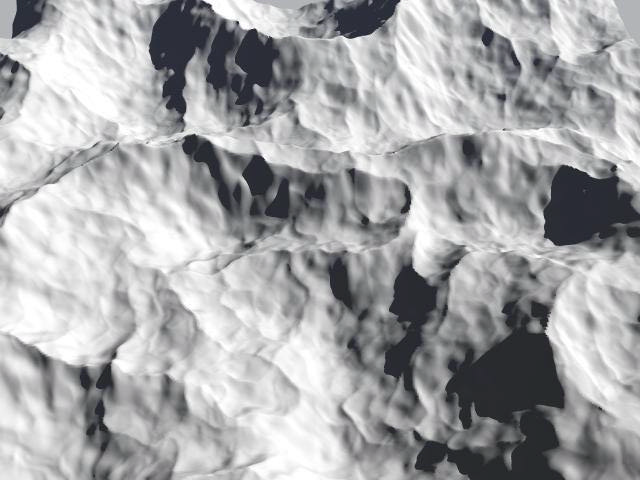

Heterogeneous fBm

source: Ken Musgrave

source: Ken Musgrave

Today: Bézier Curves

Overview

Geometric Modeling

- How did we model geometry so far?

- Direct modeling: meshes (explicit), spheres, cylinders, planes (implicit)

- Procedural modeling: L-Systems, Terrains, etc.

- Now: Brief introduction to freeform curves

- Applications in Graphics

- Camera paths, animation curves, fonts, CAD design, blending, etc.

- Applications in Graphics

Example: Camera Path

Example: Animation Curves

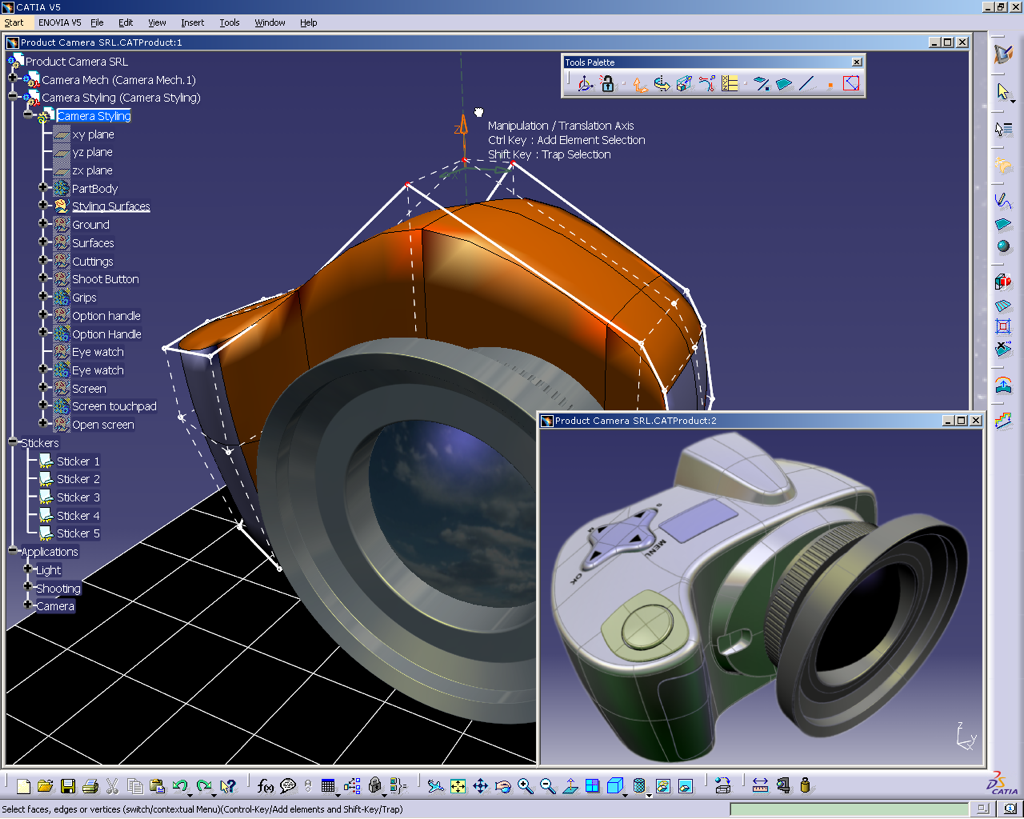

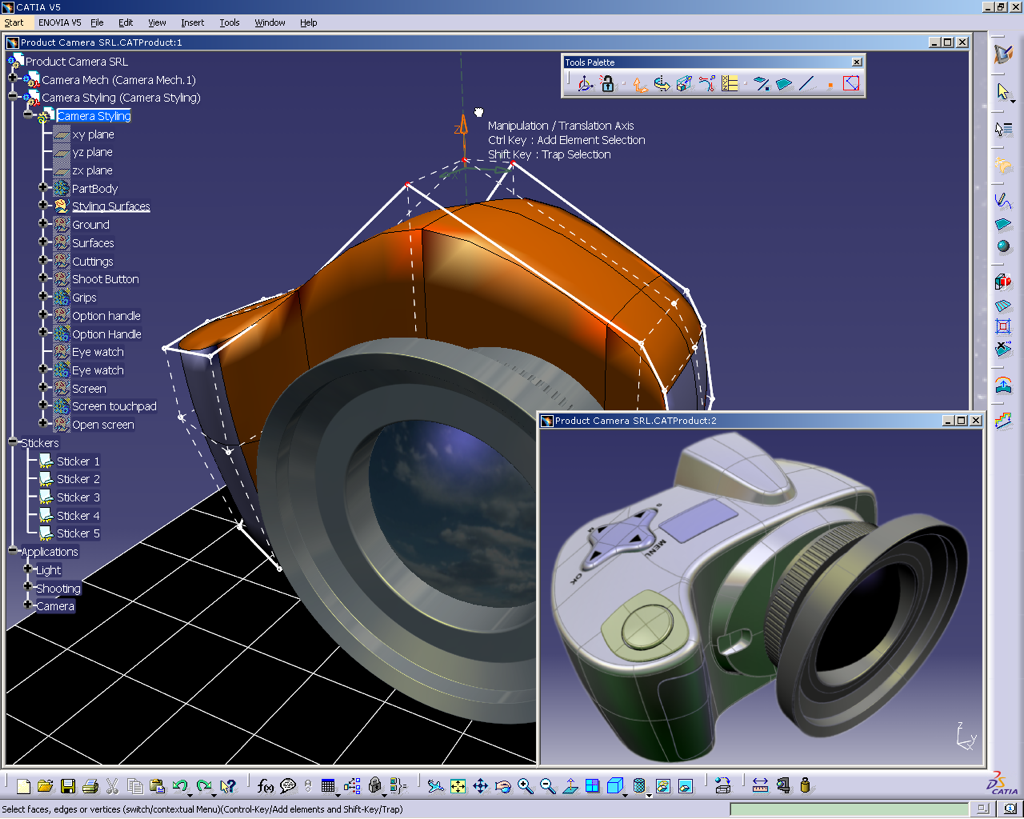

Example: Dassault’s CATIA

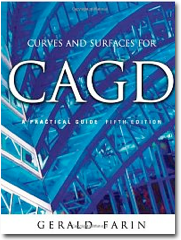

Literature

- Farin: Curves and Surfaces for CAGD. A Practical Guide, Morgan Kaufmann, 2001

- Chapters 4 & 5

Requirements

- Which properties are important for a geometry representation?

- Approximation power

- Efficient evaluation of positions & derivatives

- Ease of manipulation

- Ease of implementation

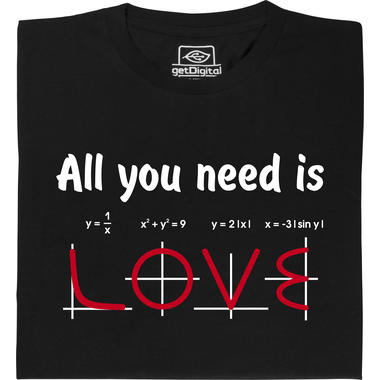

How to make LOVE?

Parametric Curve Representation

Parametric representation \(\vec{x} \colon [a,b] \subset \R \to \R^3\) (or \(\R^2\)) \[\vec{x}\of{t} = \matrix{x\of{t} \\ y\of{t} \\ z\of{t}}\]

Curve is defined as image of interval \([a,b]\) under parameterization function \(\vec{x}\).

Parametric Representation

- Parametric representation \(\vec{x}\of{t} = \transpose{\left[ x\of{t} ,\, y\of{t} \right]}\)

Guess the shape of the curve!

\[\vec{x}\of{t} = \matrix{\sin^3(t) \\ \frac{1}{16}(13\cos(t) - 5 \cos(2t) - 2 \cos(3t)-\cos(4t))}\]

Guess the shape of the curve!

Tangent Vector

- Parametric curve representation \[\vec{x}\of{t} = \matrix{x\of{t} \\ y\of{t} \\ z\of{t}}\]

- First derivative defines the tangent vector \[\vec{t} = \vec{x}’\of{t} := \frac{\mathrm{d} \vec{x}\of{t}}{\mathrm{d} t} = \matrix{ \mathrm{d}x\of{t} / \mathrm{d} t \\ \mathrm{d}y\of{t} / \mathrm{d} t \\ \mathrm{d}z\of{t} / \mathrm{d} t}\]

Tangent Vector

- Example: \(\vec{x}\of{t} = (1+\cos(t)) \matrix{\cos(t) \\ \sin(t)}\)

Discrete Curves

- Approximate the curve by a polygon, e.g. for rendering

- Sample parameter interval: \(t_i = a + i\Delta t\)

- Sample curve: \(\textbf{x}_i = \textbf{x}(t_i)\)

- Connect samples by polygon

Polynomial Curves

\[ \vec{x}(t) = \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i \, \phi_i(t) \;\in \Pi^n\]

- Ingredients

- Vector-valued coefficients \(\vec{b}_i \in \R^3\)

- Scalar-valued polynomials \(\phi_i \colon \R \rightarrow \R\)

- \(\{ \phi_0, \ldots, \phi_n \}\) span space of degree \(n\) polynomials

- Why polynomials?

- Can be computed efficiently on a computer (only multiplications and additions needed)

- Can approximate arbitrary functions (Weierstrass approximation theorem)

1815-1897

Polynomial Curves

Which basis functions \(\{ \phi_0, \ldots, \phi_n \}\) that span \(\Pi^n\), the space of polynomials of degree \(n\), should we use?

- The monomial basis \(\{ t^0, t^1, \ldots, t^n \}\)?

- Simple sum of points \(\vec{x}(t) = \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i \, t^i\) does not make sense

- Coefficients \(\vec{b}_i\) have no geometric meaning

- No intuitive curve manipulation

Monomial Basis

Check requirements for geometry representation:

- Approximation power ✓

- Efficient evaluation of positions & derivatives ✓

- Ease of manipulation ✗

- Ease of implementation ✓

Let’s find another basis of \(\Pi^n\)!

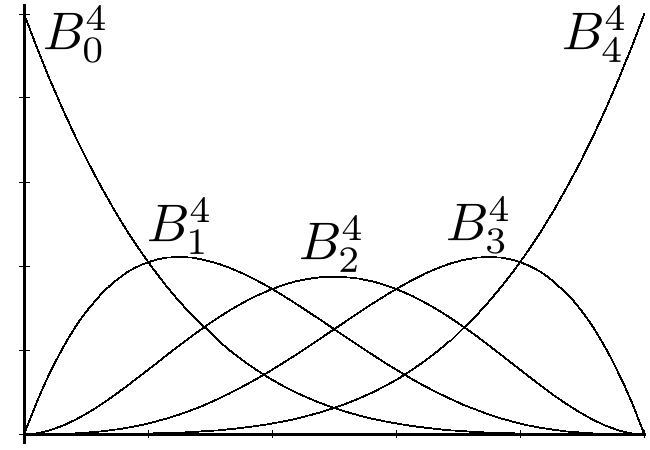

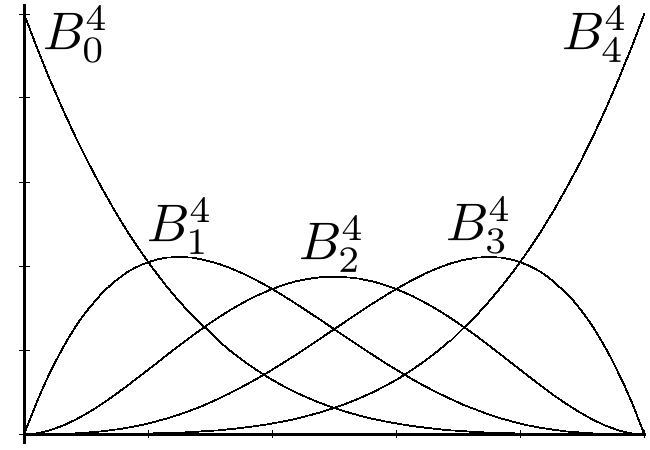

Bernstein Polynomials

\[ \begin{align*} B_i^n(t) &\;=\; \binom{n}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \,,\quad 0 \leq i \leq n\\ \binom{n}{i} &\;=\; \begin{cases} \frac{n!}{i!(n-i)!} & \text{if }0 \leq i \leq n, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \end{align*} \]

1880-1968

Bernstein Polynomials

\[B_i^n(t) = \binom{n}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i}\]

- Basis: \(\{ B_0^n, \ldots, B_n^n \}\) are a basis for \(\Pi^n\)

- Non-negativity: \(B_i^n(t) \geq 0\) for \(t \in [0,1]\)

- Endpoints: \(B_i^n(0) = \delta_{i,0}\) and \(B_i^n(1) = \delta_{i,n}\)

- Symmetry: \(B_i^n(t) = B_{n-i}^n(1-t)\)

- Maximum: \(B_i^n(t)\) has maximum at \(t=i/n\).

- Partition of unity: \(\sum_{i=0}^n B_i^n(t) = 1\)

Partition of Unity

Partition of unity: \(\sum_{i=0}^n B_i^n(t) = 1\)

Prove it!

\[ \begin{eqnarray*} 1 &=& t + (1-t) \\ &=& \left[ t + (1-t) \right]^n \\ &=& \sum_{i=0}^n \binom{n}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \\ &=& \sum_{i=0}^n B_i^n(t) \end{eqnarray*} \]

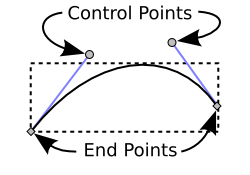

Bezier Curves

Bezier curves use Bernstein polynomials as basis: \[\vec{x}(t) = \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i \, B_i^n(t)\]

1910-1999

- Coefficients \(\vec{b}_i\) are called control points

- Points \(( \vec{b}_0, \ldots, \vec{b}_n )\) define the control polygon.

Properties of Bezier Curves

- Affine combination: Point \(\vec{x}(t)\) is an affine combination of control points. Control points have a geometric meaning!

- Follows from partition of unity of Bernstein basis

Properties of Bezier Curves

- Convex hull: Curve \(\vec{x}(t)\) lies in convex hull of control points

- Follows from partition of unity and non-negativity of Bernstein basis

Properties of Bezier Curves

- Endpoint interpolation: Curve \(\vec{x}(t)\) starts at \(\vec{b}_0\) and ends at \(\vec{b}_n\).

- Follows from \(B_i^n(0) = \delta_{i,0}\) and \(B_i^n(1) = \delta_{i,n}\).

Properties of Bezier Curves

- Symmetry: Curve defined by \((\vec{b}_n, \vec{b}_{n-1}, \ldots, b_0)\) is the same as the one defined by \((\vec{b}_0, \vec{b}_1, \ldots, \vec{b}_n)\), just in reverse order.

- Follows from symmetry of Bernstein basis

Properties of Bezier Curves

- Pseudo-local control: Control point \(\vec{b}_i\) has its maximum effect on the curve at \(t=i/n\).

- Follows from maxima of Bernstein polynomials.

Bezier Curves

Check requirements for geometry representation:

- Approximation power ✓

- Efficient evaluation of positions & derivatives ???

- Ease of manipulation ✓

- Ease of implementation ???

How to efficiently implement binomial coefficient and faculty?

\[ B_i^n(t) = \binom{n}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \quad\text{and}\quad \binom{n}{i} \;=\; \begin{cases} \frac{n!}{i!(n-i)!} & \text{if }0 \leq i \leq n, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \]

de Casteljau Algorithm

- Given:

- Control polygon \(\vec{b}_0,\ldots,\vec{b}_n\)

- Curve parameter \(t\)

- Initialization: \(\vec{b}_i^0 = \vec{b}_i \quad i=0, \ldots, n\)

*1930

- Recursion: \[ \vec{b}_i^k = (1-t)\,\vec{b}_i^{k-1} + t\,\vec{b}_{i+1}^{k-1} \] where \(k = 1,\ldots,n\) and \(i = 0,\ldots,n-k\)

- Result: \(\vec{b}_0^n = \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i B_i^n(t) = \vec{x}(t)\)

Geometric Interpretation

de Casteljau \(\leftrightarrow\) Bernstein Basis

\[\begin{align*} \vec{b}_0^1 & = (1-t) \, \vec{b}_0 + t \, \vec{b}_1 \\ \vec{b}_1^1 & = (1-t) \, \vec{b}_1 + t \, \vec{b}_2 \\[3mm] \vec{b}_0^2 & = (1-t) \, \vec{b}_0^1 + t \, \vec{b}_1^1 \\ & = \underbrace{(1-t)^2}_{B_0^2(t)} \, \vec{b}_0 + \underbrace{2(1-t)t}_{B_1^2(t)} \, \vec{b}_1 + \underbrace{t^2}_{B_2^2(t)} \, \vec{b}_2 \end{align*}\]

Bernstein Recursion

Bernstein polynomials can be evaluated through a recursion:

\[B_i^n(t) = (1-t)\,B_i^{n-1}(t) \;+\; t\,B_{i-1}^{n-1}(t)\]

with \(B_0^0(t) = 1\) and \(B_i^n(t) = 0\) for \(i \notin \{0,\ldots,n\}\)

Prove it!

\[\begin{eqnarray*} B_i^n(t) &=& \binom{n}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \\[2mm] &=& \binom{n-1}{i} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \;+\; \binom{n-1}{i-1} t^i (1-t)^{n-i} \\[2mm] &=& (1-t) \cdot \binom{n-1}{i} t^i (1-t)^{(n-1)-i} \;+\; t \cdot \binom{n-1}{i-1} t^{i-1} (1-t)^{(n-1)-(i-1)} \\[2mm] &=& (1-t)\,B_i^{n-1}(t) \;+\; t\,B_{i-1}^{n-1}(t) \end{eqnarray*}\]

de Casteljau Construction

\[\begin{eqnarray*} \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i B_i^n(t) &=& \sum_{i=0}^n \vec{b}_i \left[ (1-t)\,B_i^{n-1}(t) \;+\; t\,B_{i-1}^{n-1}(t) \right] \\ &=& \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} \left[ (1-t)\,\vec{b}_i \;+\; t\,\vec{b}_{i+1} \right] \, B_{i}^{n-1}(t) \end{eqnarray*}\]

Try it yourself!

Applications of Bezier Curves

Bezier curves are the most prominent curve representation:

- Used for 2D vector drawing applications

- Used for 3D computer-aided design (CAD)

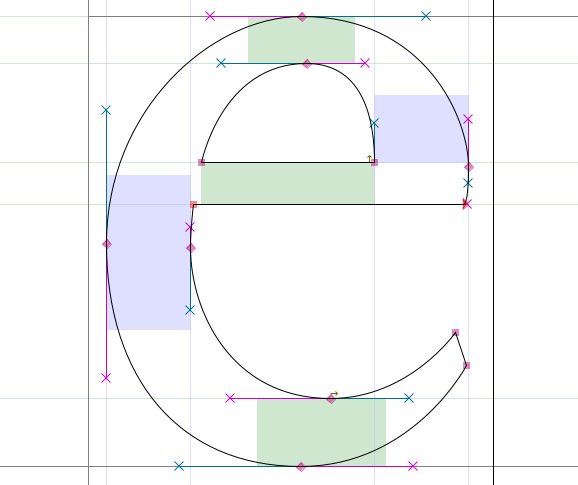

- Used for true-type fonts

Inkscape

Inkscape  Dassault CATIA

Dassault CATIA  FontForge

FontForge

Applications of Bezier Curves

Literature

- Farin: Curves and Surfaces for CAGD. A Practical Guide, Morgan Kaufmann, 2001

- Chapters 4 & 5